Wounds that fail to heal or contract in size for up to three weeks despite the use of standard care techniques are described as chronic or hard-to-heal wounds. These wounds result in increased pain and impaired mobility for patients, which translates into lost productivity and lower life quality. Some factors that contribute to delayed wound healing include disease (diabetes, peripheral artery disease, cancer), local or systemic infections, stress, prolonged use of certain medications, alcohol, smoking, and poor nutrition. However, an often-overlooked contributor is the presence of tenacious biofilm in injured tissues.

NB: Wound conditions differ between patients and must be managed by competent wound experts. This article is a product of research and may not be considered overarching medical advice. For more information, contact The Wound Pros today.

How Biofilm Affects Wound Healing

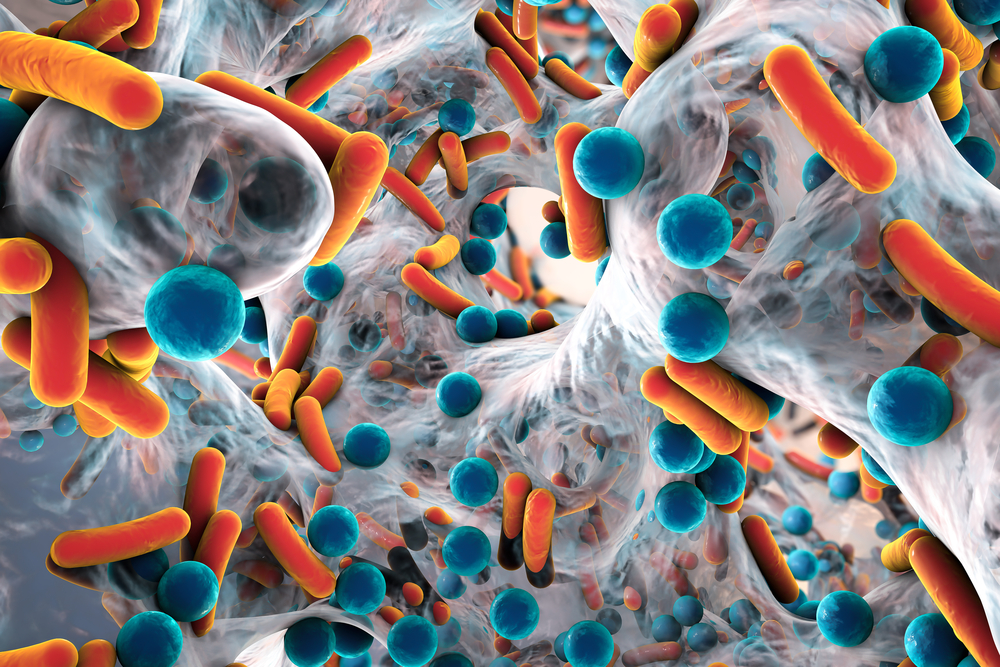

Biofilm refers to communities of microbes, such as bacteria, fungus, and other microscopic organisms assumed to be present in chronic or hard-to-heal wounds. The World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) remarked that "all non-healing chronic wounds potentially harbor biofilms, and, therefore, relying on anecdotal visual cues is unnecessary." "Instead, clinicians should assume all non-healing, chronic wounds that have failed to respond to standard care have biofilm. Therefore, treatments should be targeted towards effective disruption of biofilms and preventing formation and reformation." Because open wounds lack the natural protective cover of the skin and acid mantle, microorganisms present on the skin's flora or from endogenous sources can gain access into subcutaneous tissues and proliferate over time. Also, when biofilm matures and establishes itself, it exhibits firm resistance to antimicrobial agents and the host's immune defense.

Research has shown that biofilm impairs wound healing in chronic wounds by increasing the risk of infections, impeding fibroblast proliferation, and inflammatory responses, as well as lowering the efficacy of antimicrobial therapies. Since hard-to-heal wounds place an enormous financial burden on healthcare, addressing known contributors, including biofilm, is critical for improving healing outcomes and avoiding limb amputations. It is also worth noting that timely and adequate wound hygiene can greatly reduce the rate of chronic infection, antibiotic usage, and the need for specialist or advanced treatments.

Biofilm Management and Wound Hygiene

Biofilm management involves the removal of biofilm from the wound and taking active measures to prevent its re-formation. The concept of wound hygiene is closely correlated; it is aimed at removing unwanted materials from the wound (including biofilm), necrotic or devitalized tissues, debris, etc., to facilitate healing. These strategies can be classified into four main activities; cleansing, debridement, re-fashioning the wound edges, and application of dressings.

Cleansing

The first step in a wound hygiene procedure is cleansing the wound bed and peri-wound skin following an injury using a sterile gauze containing an antiseptic or antimicrobial agent. Cleansing decontaminates the wound bed and surrounding areas, removes debris and biofilm, and also loosens devitalized tissues. Alternatively, a surfactant solution can be used, with the clinician applying gentle force over the wound using cleansing pads or medical wipes. The objective of cleansing is to decontaminate the wound and prepare it for debridement. The area of skin 10-20 cm away from the wound edges should be cleansed using saline solution to reduce bacterial load.

Debridement

Following injury, biofilm can form quickly in the first few hours and mature over the next 48-72 hours. Debridement is essential to protect the wound bed and mitigate microbial intrusion with the subsequent application of a dressing. Sharp, mechanical, ultrasonic, and biological debridement are all viable techniques for removing devitalized tissues from the wound site. Applying firm pressure is usually encouraged to dislodge any biofilm that may have begun to form up to the extent of pinpoint bleeding to promote faster wound healing. However, care should be taken for lower extremity wounds with inadequate perfusion or autoimmune problems. Debridement should be performed while taking into account the patient's skin integrity and pain tolerance and instruments must be sterile. Regular debridement should be considered standard practice in the management of hard-to-heal or chronic wounds.

Re-fashioning

The removal of overhanging, callused or rolled up wound edges that may harbor biofilm follows debridement. To promote faster wound contraction and epithelial advancement, the edges should be aligned with the wound bed. Exposure of viable tissues and pinpoint bleeding is desirable.

Dressing

Applying wound dressings is the last phase of a proper wound hygiene program. The choice of dressing will depend on several factors including the cause of and type of wound, drainage, and skin integrity. Dressings should help protect the wound and provide a moist environment needed for faster healing. Wound dressings containing antimicrobial agents, e.g., povidone-iodine, Polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB), and silver can prevent biofilm reformation. The amount of exudate also plays a key role in choosing a dressing. Clinicians must make sure to continually assess the wound as it progresses and change dressings every few days until it heals completely.

.webp)

.avif)